Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Six: Ensuring High-Quality Artefacts

Pre-empting the needs of centres, as well as applying the vacuum-effect described above, Akong Rinpoché put much effort into making sure that Samye Ling, and later the Samye Dzongs, be properly equipped with all the material supports they would need. Once again, this often involved overcoming an initial reluctance on the part of centre people, usually overawed by the expense or scale of his wishes, which were based on future-proofing rather than current needs. In all cases known to the author, this initial reluctance was always, with time, replaced by a great gratitude as, day after day, people in the various centres enjoyed their beautiful buddha statues, using their high-quality ritual instruments and so forth.

Concerning the religious images—statues, stupas or thangkas—Rinpoché showed a double concern. He wanted their facture to be to the highest of standards but also the spiritual presence to be of the most value. For him an image had little value, no matter how well-made or beautiful, if it was not properly consecrated and had not become the home of true relics. He often stressed the point that it is not the statue that counts but what is inside it.

Concerning the religious images—statues, stupas or thangkas—Rinpoché showed a double concern. He wanted their facture to be to the highest of standards but also the spiritual presence to be of the most value. For him an image had little value, no matter how well-made or beautiful, if it was not properly consecrated and had not become the home of true relics. He often stressed the point that it is not the statue that counts but what is inside it.

For the centres, Rinpoché would often do the shopping himself, in Nepal, where he came to be known by the best statue-dealers and statue-makers (for the larger ones). For the Samye Temple, Rinpoché commissioned a central Buddha Sakyamuni statue from the most famous statue coppersmith in the famous Patan area of Nepal, the traditional home of the finest image-making. Along with the Buddha image, he commissioned standing statues of disciples Mahamaudgalyana and Shariputra. I had the pleasure of checking on the progress of these during a visit to Nepal in 1987. Unfortunately the famous artisan had decided to retire and had entrusted the work to his son, who in turned was overwhelmed by unexpected, last-minute orders from Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoché. Little had been done and I was just shown plans. This was less than a year before the temple opening.

When the statues eventually arrived in Samye Ling, Rinpoché found them not at all up to standard and saved the situation (the temple was soon to be opened) by having a new head made for the Buddha by Dolma Jeffries, Sherab Palden’s senior student. In general, Rinpoché spoke of himself as someone who "knew very little" and was "a very ordinary person". In reality, he was someone of exceedingly fine aesthetic taste when it came to art or to craft. This fine taste was to come to its apogee in his last decade of life, as he commissioned thangkas and statues for Dolma Lhakang in Tibet, by which time some of the best craftsmanship was to be found no longer in Nepal but in the large Tibetan community in Chengdu, Sichuan.

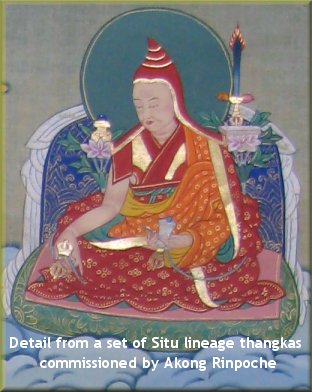

From the earliest years he had shown concern that the very high standard of artwork executed by Sherab Palden Beru, in the 1970s, be maintained and, to this end, had encouraged the creation of an art school around Sherab so that people could learn in the slow, traditional way, as apprentices to a master. In the later years, Rinpoché sought out the very best artists from Palpung and Chengdu and made very clear to them the finesse and detail he required of them. The resulting work set a standard in thangka painting and statue-making, so much in contrast with the poor standard of work he had seen emerging from Nepal and India in the 1970s and 1980s.

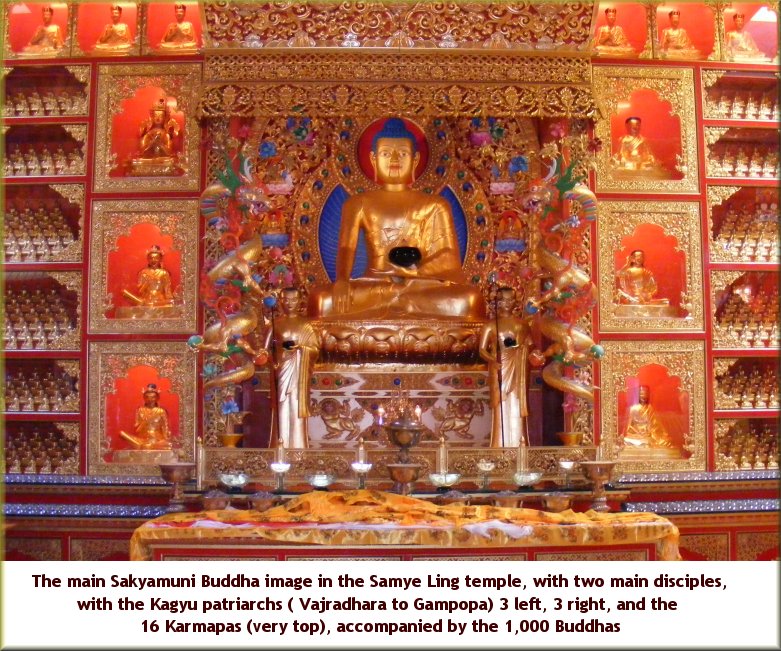

Also for the Samye Temple, Rinpoché ordered some one-third-life-size statues of the first six Kagyu patriarchs, in metal, had made statues of the first sixteen Karmapas and also set up a statue-casting project in Samye Ling to cast the “one thousand buddhas of the golden age”. The casting workshop also produced many ornate items for the temple, while at the same time creating moulds and templates that could be used later in other temples in the Samye Dzongs.

With Sherapalden, he set the art studio onto the task of painting major thangkas for the Temple, mainly depicting the great Buddhist masters of India and the Kagyu lineage masters, as well as those of the four Maharaja divinities seen as protectors of the world. From metal-smiths he ordered, for the temple, prayer-wheels, to be driven by electrical mechanisms and to be filled with mantras either micro-printed or on microfilm. The idea of one wheel was to have one mantra for each human being on Earth.

While ordering some wood-carving for the first-floor shrine from the world’s finest Tibetan wood-carver, in Asia, Rinpoché also set in motion the wood-carving workshop to produce artefacts for the temple, such as the dragons that flank the main Buddha image or the large wooden temple drums. A silk-screen printing workshop was set up to print the dragon and crane ceiling panels for all floors of the temple building. A weaving workshop was also set up. From 1979 through 1988, Samye Ling became, under Rinpoché, a fascinating gathering of skilled craftspeople all focused on the one project. It was very evocative of the ancient times in Europe of cathedral-building.

Rinpoché himself was very present, maintaining enthusiasm, encouraging diligence and always trying to achieve the highest standard of work possible. The above highlights one very important overall aspect of Rinpoché’s dharma work: that of transmission through apprenticeship. Whether it be meditation, Buddhist studies, ritual arts such as instrument-playing or torma-making or more general Tibetan arts and crafts, he believed in a living transmission that would serve a double function:

Rinpoché himself was very present, maintaining enthusiasm, encouraging diligence and always trying to achieve the highest standard of work possible. The above highlights one very important overall aspect of Rinpoché’s dharma work: that of transmission through apprenticeship. Whether it be meditation, Buddhist studies, ritual arts such as instrument-playing or torma-making or more general Tibetan arts and crafts, he believed in a living transmission that would serve a double function:

![]() Only by a hands-on learning process, under the guidance of an expert, would the new audience learn correctly.

Only by a hands-on learning process, under the guidance of an expert, would the new audience learn correctly.

![]() At the same time, the process of transmission would help preserve the ancient wisdoms and skills.

At the same time, the process of transmission would help preserve the ancient wisdoms and skills.

Akong Rinpoché put great care and effort into the consecration of these images, either doing it himself or having it done by visiting great masters. Thus, not only were the images properly blessed but also these masters left something of themselves in Samye Ling or, later, the other centres in which they were requested to consecrate objects. Rinpoché himself said, on various occasions,

“You do not realise what a sacred place this temple has become, due to the great masters that have visited here, taught and given transmission. In the East, solely due to that fact of their presence and activity, this would be now a place well worthy of pilgrimage.”

Rinpoché was keen to have particularly powerful “presences” at key points in Samye Ling, established according to the Tibetan science of sa bcad, "earth energies". Besides the treasure-vases buried beneath the temple, he asked the Tai Situpa to place some rare relics in the dharmachakra symbol on the top floor of the temple building and Rinpoché himself had a vajra from Guru Rinpoché embedded in the wall above the main entrance to the Samye Project, only months before his death. Rinpoché also consulted at length with the Tai Situpa concerning the location of the major stupa at Samyé Ling, as its new presence would bring a change to the energy balances in the centre. The present location was chosen to bring balance between the Samye Project and what was, at the time, the retreat centre at Purelands. Not to mention the naga house, in the river.

......continue to the next part of the story: The Temple Opening