Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Fifteen: Establishing the Kagyu Mahamudra Trainings...Part 1

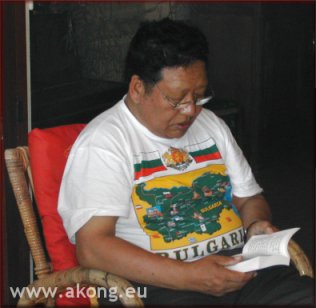

These teachings centre on an awakening to the true nature of mind, understanding that to also be the true nature of all realities. A master of Mahamudra, such as Akong Rinpoché, may bring someone to a readiness for that awakening in all sorts of ways: that ability, indeed, is the sign of the prowess of a true master. Never leaving the sphere of awakened clarity, a Mahamudra guru

senses the skilful ways to bring a person in confusion to a recognition of ultimate truth, whenever and however it is possible.

Such a master has the power to give a “pointing-out” [1], temporarily "holding" the disciple—who has made the preparatory steps necessary for their mind to be opened to the own dharmakaya nature—in most profound meditation of the buddha nature. The preparation required can take a traditional route, via the Four Ways of Changing the Mind, the Four Special Foundations, Yidam practice and so forth. The yidam practice may be replaced by a special, formalised shamatha and vipasyana training,

such as that of Mahamudra, Ocean of

Definitive Meaning. But it can take many other ways too.

These teachings centre on an awakening to the true nature of mind, understanding that to also be the true nature of all realities. A master of Mahamudra, such as Akong Rinpoché, may bring someone to a readiness for that awakening in all sorts of ways: that ability, indeed, is the sign of the prowess of a true master. Never leaving the sphere of awakened clarity, a Mahamudra guru

senses the skilful ways to bring a person in confusion to a recognition of ultimate truth, whenever and however it is possible.

Such a master has the power to give a “pointing-out” [1], temporarily "holding" the disciple—who has made the preparatory steps necessary for their mind to be opened to the own dharmakaya nature—in most profound meditation of the buddha nature. The preparation required can take a traditional route, via the Four Ways of Changing the Mind, the Four Special Foundations, Yidam practice and so forth. The yidam practice may be replaced by a special, formalised shamatha and vipasyana training,

such as that of Mahamudra, Ocean of

Definitive Meaning. But it can take many other ways too.

Once the first awakening has happened, the disciple needs to learn, under their guru’s guidance, how to return more and more frequently to the experience, how to make it last longer and how to keep it pure and authentic. The guru whose help makes someone recognise that perfect nature for the first time becomes their “root guru”, by definition. A very fortunate few of us, who had done the prior training, had the blessing of such an awakening by Akong Rinpoché in the mid-1970s. Akong Rinpoché became the root guru—in that strict sense of the term—for some people but, given the very private and personal nature of “pointings out” and such awakenings, it is impossible to know how many people, until each tells their story. As not that many people reach the stage of “pointing out”, the number is necessarily limited. However, despite the relatively limited numbers, it is mentioned here among his qualities as it is the most sacred task a dharma-master can perform.

In general, Akong Rinpoché was one of the first Tibetan gurus to discover the differences and the similarities between Tibetans and the Westerners who came to him. He found the Westerners to be usually more sensitive than Tibetans but, at the same time, less stable. He often used the omnipresent rainbows of the hippie era to point out that this symbol of something most beautiful and attractive (in their eyes) is also the symbol of impermanence and unreliability. In the earlier years, Rinpoché was keen for people to know about the Kagyu lineage, the example of Milarepa, the power of faith and so forth. As time went by, he saw how relatively fickle were the minds of many of the people he was teaching (myself included, of course). The profound promises and commitments of one year were forgotten the next. He came to the conclusion that barely anyone was yet ready for the real commitments implied in Vajrayana practice: those between a root-guru and a disciple or those of the fourteen main precepts of tantra and so forth. For that reason, he became unwilling to become or be considered a “guru”:

“Many of you speak of me as a guru or want me to be your guru and you to be my disciples. But that is very difficult. You need to understand the real qualities of a true guru and the qualities of a true disciple. I do not have those. You do not have those. I prefer to be your friend. Just consider me as a friend, trying to help you, and that will be better for all of us.”

It says of real Vajrayana guru that it is a fault for them not to teach Mahamudra to someone who is ready and it is also a fault to teach it to someone who is not ready. Akong Rinpoché was the perfect exemplar of someone who adhered to this guideline. In one or two cases, where he obviously knew of a person’s karmic ripeness, he would awaken their buddha nature through a very fast-track route or sometimes tell someone he met for the first time, to their great surprise, to drop everything and that the only thing they should do in this life was long retreat: something very atypical of his general style, which encouraged a safe-and-sure, step-by-step training. He was responding to what was, to him, the obvious readiness of those people.

By contrast, he utterly refused to give “deeper” teachings just because people wanted them or asked repeatedly for them. He often said things like the following:

“You keep on asking me to do more courses and expecting new teachings but, as far as I can see, you aren’t practising the teachings I’ve already given you. Even if I have to repeat the same things again and again, I feel it is my duty to keep telling you about being more humble, more kind, more mindful and so on until I actually see you are doing those things and that you are really listening to my teachings and taking notice of them. Until then, there is no point expecting more. I would just be wasting my breath and wasting your time. For you, teachings are more like entertainment. You don’t take them seriously enough or understand that they are there to help you, not me.”

Akong Rinpoché treasured all the buddhadharma, on all its levels, but it must be said that the Mahamudra teachings were very close to his heart. Mahamudra exists as two aspects:

![]() Sutra Mahamudra, which is anything about it that can be taught through words and concepts, sometimes in public, and

Sutra Mahamudra, which is anything about it that can be taught through words and concepts, sometimes in public, and

![]() Actual Mahamudra, which, being directly experiential and not conceptual, can only be practised and which was traditionally taught on a one-to-one basis. In order that Mahamudra be properly understood, Rinpoché asked his visiting teachers to explain texts like the IIIrd Karmapa’s Mahamudra Prayer, Jamphel Bengar Zangpo’s Short Prayer to Vajradhara or Kongtrul’s

Ground, Path and Fruition, along with their commentaries. He also always keenly encouraged people to read the lineage masters’ biographies.

Actual Mahamudra, which, being directly experiential and not conceptual, can only be practised and which was traditionally taught on a one-to-one basis. In order that Mahamudra be properly understood, Rinpoché asked his visiting teachers to explain texts like the IIIrd Karmapa’s Mahamudra Prayer, Jamphel Bengar Zangpo’s Short Prayer to Vajradhara or Kongtrul’s

Ground, Path and Fruition, along with their commentaries. He also always keenly encouraged people to read the lineage masters’ biographies.

In the reality of Mahamudra training, there are what is known as the “foundations” ('ngondro ... sngon ‘gro), followed by the “actual practice” (ngözhi ... dngos gzhi). Akong Rinpoché had set a few people onto completing the eight foundation practices in the first years of the 1970s, giving personal instruction in each practice himself. Following a request from Katia and myself for training in the sequential meditations of Mahamudra, Ocean of Certainty, Rinpoché said he was prepared to teach them to us but that it would need to be in private/in secret. His suggestion for this was that the three people he considered ready for Mahamudra training at that point—myself, Katia and Magnus Weschler—receive regular training from him and practice sometimes together, with him also present at times, in the newly-acquired Old Johnstone house next door to Samye Ling, in its attic shrine room, once it was ready. This plan never concretised, for a few reasons, but it showed Rinpoché’s willingness to teach if the students and circumstances were correct.

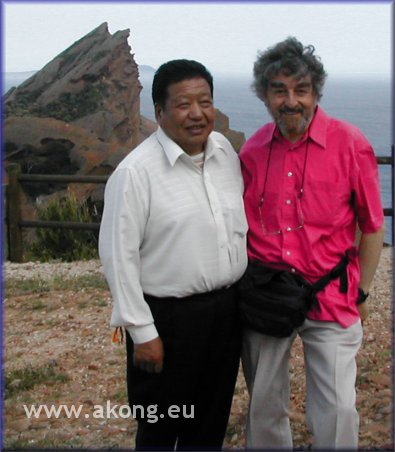

As it was, we each received Mahamudra meditation instructions from him individually, with him becoming our root-guru in late 1975 and early 1976. The impression that we had was of being the first Westerners to receive this most sacred of transmissions from him but, given the secret nature of such teachings, we will never know if that was the case or not. As various masters, such as Tulku Urgyen, famous for their nature-of-mind meditation came to Scotland, Akong Rinpoché would sometimes set up special circumstances for me to receive confirmatory transmissions from them. He also asked them to give me any special advice they thought might be helpful in that direction. Although it was embarrassing at times to be put in prominence like that, he would make it easier by telling visiting teachers that I was his “Mahamudra idiot”and this opened up a complicity with them that was very helpful for both my personal understanding and for translating the texts, as the teachers felt free to explain things on a deep level when appropriate and also felt free to slip out of the more formal and expedient dharma teaching structures to present things in a less formal, more relaxed way—the way they themselves experienced it.

Akong Rinpoché’s trust in us in this area was a great responsibility and a great blessing. In 1981, when the Gyalwang Karmapa passed briefly through London, Akong Rinpoché set up a special meeting. It was memorable, as it took place in the evening in a Thames-side boathouse, related to the property of Joe Gelpey, who was hosting the Karmapa. Ken and Ingrid McLeod, in London to see the Karmapa, had just completed the first three-year retreat in Pleige and Rinpoché wanted us two couples to meet up to compare notes and to discuss insights, realisations in our respective meditation experiences—us through Mahamudra drol-lam and them through the tap-lam. It was very pleasant to do this and very interesting. Akong Rinpoché was curious to know the conclusion of our discussions and remained curious throughout the following thirty years, as people trained in Mahamudra or came out of the long retreats. He wanted to see which methods worked best for Westerners, as well as which difficulties they encountered and which benefits they found.

[1] Tibetan : ngo ‘phrod, literally « recognition of essential character » but most generally translated these days as « pointing out ». The Tai Situpa has quipped that this is a strange translation, as there is nothing to point to, to point out.

.....this narrative continues: Establishing the Mahamudra training... contd.