Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Three: A Leader & an Inspiration

The story of the material development of Samye Ling and its branches is a very rich, complicated and colourful one, full of fascinating anecdotes. It is a separate tale that needs to be told in its own right . This paper focuses on Akong Rinpoché’s role rather than Samye Ling itself, although in some ways the two are inseparable.

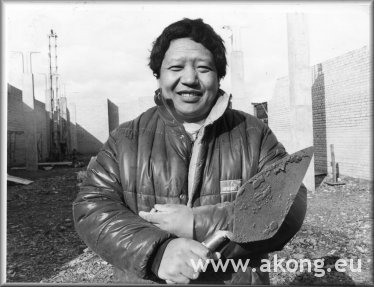

Rinpoché was totally present throughout all stages of the conception and development of Samyé Ling and indeed Holy Isle too, directing the design, organisation, implementation, labour problems, related artwork and the associated spiritual aspects, such as sacred site preparation and final consecration. He was equally the heart and soul of all the Samye Ling and Samye Dzong projects in various countries. This omnipresence was much more than the anecdotal role sometimes shown in some TV documentaries or described in personal accounts, which focus on his own presence—trowel or shovel in hand—on a building site, as someone “joining in” with the workers, despite his elevated status. Rather than joining in with something, he was the something.

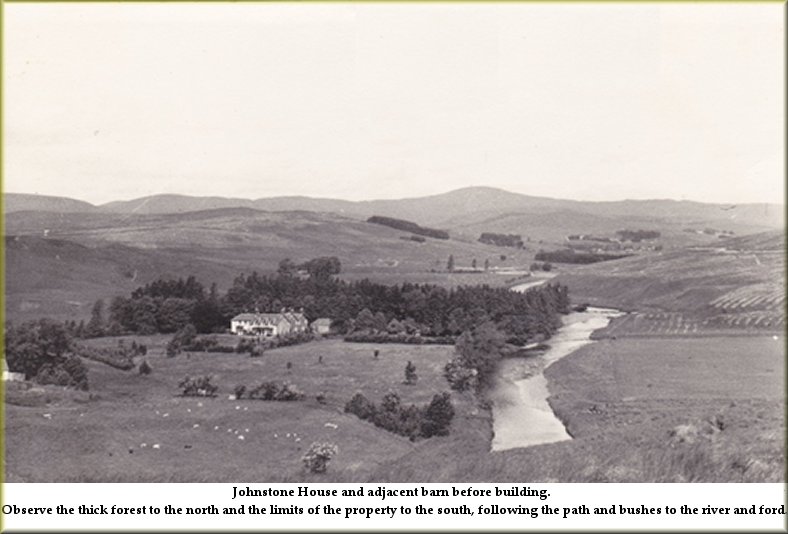

Rinpoché often said that he was a Tibetan and that Tibetans hold much more trust in real estate and goods than in artificial currency. Throughout his life, after that initial hesitation, he encouraged his centres to buy rather than rent their properties and to establish good material assets that would serve as a basis for expansion later. Johnstone House had initially come with a minimal amount of land, just an acre or so, being bounded by the road and the river to the west and east and by the adjoining properties of Old Johnstone and Maiden’s Cottage to the south and north (see photo above). With the future in view, Rinpoché did not hesitate in borrowing money and buying the adjacent land as soon as it became available. Mr Maiden was our next-door millionaire and his cottage, beautifully lined inside with wooden fir walls, eventually came on the market in the early 70s, along with the adjacent field. Its purchase enabled Rinpoché to move out of his upstairs room in Johnstone House and to have some autonomy.

Old Johnstone, to the south, was owned by two elderly sisters who kept sheep. When one of them became too old to continue, they both decided to sell up. The property with its acres of land was beyond Rinpoché's budget, even with borrowing, and a solution was found when Rinpoché’s friend and disciple, Magnus Wechsler, made a deal with him to buy the properties (two small adjacent cottages that he fused into one dwelling) and to let Samye Ling buy most of the land. Another property, known at the time as “Sevens” , was bought by Ani Pema (formerly Josie Wechsler) , another long-term friend and disciple of Rinpoché from the London and Oxford days. She bought it with a view to dwelling there for as long as she was able and then ceding it to Samye Ling at a time when she would be better served by living in Johnstone House. This property, extended and rebuilt several times under Rinpoché’s direction was to become the first long-term retreat centre of Samye Ling. It is now known as “Purelands”.

The above is mentioned to help

awareness of some aspects of Akong Rinpoché’s attitude towards

property and its development. He was, at times, subject to

some criticism for the way in which Samye Ling developed, under

him, in somewhat of an architectural chaos. He had

been advised in particular, by a Scottish architect who

spoke frequently with him in earlier times, to make a

master-plan and to determine a single style that would apply

throughout in the years to come. But that was not

Rinpoché's way. The style of the “new building” (the first

major addition) differed from that of Johnstone House. What is

now the Tibetan Tea Rooms and Shop complex was originally

second-hand, prefabricated-panel buildings. The Lotus Lodge

block came from second-hand, portable site accommodation

buildings joined together and upgraded by Samye Ling building

staff. Individual dwellings of various styles were allowed to be

constructed in the grounds and so on and so forth. The magnus

opus, Samye Project, had yet another, very distinctive style.

Although the question of very tight budgets in part determined

this, several key points were very indicative of Rinpoché’s

approach:

The above is mentioned to help

awareness of some aspects of Akong Rinpoché’s attitude towards

property and its development. He was, at times, subject to

some criticism for the way in which Samye Ling developed, under

him, in somewhat of an architectural chaos. He had

been advised in particular, by a Scottish architect who

spoke frequently with him in earlier times, to make a

master-plan and to determine a single style that would apply

throughout in the years to come. But that was not

Rinpoché's way. The style of the “new building” (the first

major addition) differed from that of Johnstone House. What is

now the Tibetan Tea Rooms and Shop complex was originally

second-hand, prefabricated-panel buildings. The Lotus Lodge

block came from second-hand, portable site accommodation

buildings joined together and upgraded by Samye Ling building

staff. Individual dwellings of various styles were allowed to be

constructed in the grounds and so on and so forth. The magnus

opus, Samye Project, had yet another, very distinctive style.

Although the question of very tight budgets in part determined

this, several key points were very indicative of Rinpoché’s

approach:

• He was by nature thrifty and happy to be so, declaring himself old-fashioned inasmuch as he he could not bear to throw things away if there was still some use in them. Rinpoché came from a land and an age where material objects were much rarer than in the West and therefore more valued. He was a natural recycler, from the earliest days of making a new bedsheet for Samye Ling from two torn ones or from the early 1970s expeditions to the junkyard in Dumfries to buy discarded blankets all the way through to the end.

• He “played things by ear”, moment by moment, day by day, year by year, rather than having a fixed and clear vision of how everything was going to be. His way of dealing with things was very organic and hands-on. A master-plan would have been an uncomfortable constraint for him. Indeed, in the one area where there was supposed to be a master-plan—that of the Samye Project—he brought constant updates and changes, each of which needed to be drawn anew by the architects and submitted for planning permission. The actual evolution of the project and the plans showed him where to go next or what was still needed. This step-by-step, back-to-the-drawing-board approach was typical of him (see following point) and often very trying for those working with him.

• He was a perfectionist who would not hesitate to have even a large percentage of work done be taken apart, so as to be done slightly differently—when that “slight difference” was an important one, for him. He saw buildings or other works done as being things that would be used for a long time in the future. The tiresome work of dismantling and re-bulding was relatively-short-term, in his opinion, compared to the time of benefit of the changes made. Needless to say, his perfectionism tested the patience of many of those working under him, whether it meant re-typing a whole document (in the pre-computer days), rebuilding a wall or taking apart and re-sewing a garment. Thus, it taught them patience, respect, mindfulness and diligence. This having been said, he would also know when enough effort had been spent on something and that it was time to give up trying to attain a perfection that proved unattainable and to invest time and effort elsewhere where it could be better used: a pragmatic perfectionist rather than an obsessional one.

• He had a natural curiosity and truly enjoyed his designing and building adventures, happy to learn in a trial-and-error way. When he watched TV, one of his preferences was for programmes showing how things were made, in factories, in laboratories and so on. With those and nature documentaries and so forth, he was in constant education and one that compensated for material things not learned during his own monastic education. He was also constantly on the lookout for what could be of use, either for his European or African projects but especially in Tibet. His deep interest in biodynamic agriculture was one example of this.

Rinpoché often used the term “achievement” or “accomplishment” and loved to see a material outcome for work done. It was perhaps partly for that reason that he did truly enjoy building or gardening work or other tasks, such as the sewing he spent so much time doing in the first years of Samye Ling, making clothes and repairing sheets and towels. His own account of his frequent presence on the building site was that it made other people come along, during the days of the temple construction when all the workers were volunteers. Whether through inspiration or guilt, it was true that his presence magnetised people into going out, often into the freezing cold, to lend a hand.This brings us to one very important aspect of Rinpoché as a teacher by example and presence, as mentioned above. In the physical work he performed—at Samye Ling or in other places, such as the Dhagpo Kagyu Ling centre in the 1970s—Rinpoché set a wonderful example in many areas but in three in particular:

1. That of diligence, working tirelessly and with a great sense of commitment to the task, sometimes telling others that such was needed when working for the common good and the future benefit of everyone. He would often return to his residence totally exhausted and with many aches and pains, troubling his medical advisors who were aware of his growing arthritis and other ailments. His words and his presence constantly exuded one key message,

“Do not waste your time! Do something useful and meaningful.”

His example (in Dhagpo, for instance) showed people that joyful enthusiasm could replace a natural tendency to procrastinate.

2. That of mindfulness, working with tremendous presence, gentleness and one-pointed yet relaxed concentration.

3. That of the courage of faith, undertaking enormous and sometimes seemingly-impossible tasks, feeling that one needed to start somewhere and that if a thing had the karma to happen, it would draw to it the people, the energy, the funds and other resources.

......continue to the next part of the story: faith and the vacuum effect