Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Four: Faith and the Vacuum Effect

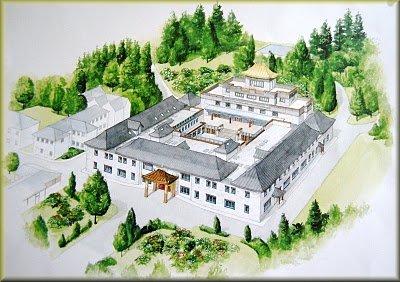

The earlier period of the Samye Project met with some questioning, not to say criticism. Working with Peter Lebaski—the first of several architects involved with the project—plans had been drawn up for the new complex: a quadrangle comprising a temple, lecture halls, museum, libraries, dining area and accommodation. The author had the pleasure of making for Rinpoché the first rough 3-D model of Peter’s drawings, in painted clay, exhibited in Samyé Ling office for a couple of years in a small, perspex cabinet.

Realising the scale of the project, some of the residents or visitors thought it too grand and not at all corresponding to the numbers frequenting Samye Ling at the time. It seemed a bit like a folie de grandeur to them or simply a waste of time and money. This criticism was to come back again and again over the years, especially from those who wanted a dharma that was low-key

and simple. Rinpoché’s own attitude, adapted to this next period of Samye Ling, was the total reverse of the wait-and-see attitude he had formerly adopted and he started speaking, on many occasions, of the first fifty years of Samyé Ling as being a time of putting something into place for future generations. He told the community that it was not working for its own needs and benefit and that its members may actually never themselves be around to enjoy those benefits (alas, this became

so true!): we were working for those yet to come and had to accept that fact. We needed to become used to living in a constant building-site rather than a tranquil meditation centre. His fifty-year calculation was pretty spot-on, the main work of Samye Project being completed weeks before his death and some forty-six years after the founding of the centre.

Realising the scale of the project, some of the residents or visitors thought it too grand and not at all corresponding to the numbers frequenting Samye Ling at the time. It seemed a bit like a folie de grandeur to them or simply a waste of time and money. This criticism was to come back again and again over the years, especially from those who wanted a dharma that was low-key

and simple. Rinpoché’s own attitude, adapted to this next period of Samye Ling, was the total reverse of the wait-and-see attitude he had formerly adopted and he started speaking, on many occasions, of the first fifty years of Samyé Ling as being a time of putting something into place for future generations. He told the community that it was not working for its own needs and benefit and that its members may actually never themselves be around to enjoy those benefits (alas, this became

so true!): we were working for those yet to come and had to accept that fact. We needed to become used to living in a constant building-site rather than a tranquil meditation centre. His fifty-year calculation was pretty spot-on, the main work of Samye Project being completed weeks before his death and some forty-six years after the founding of the centre.

As mentioned in the previous section, he led by example—diligence and his courage of faith. The author recalls one of his first encounters with the latter, one day when driving Rinpoché back from Dumfries and discussing the forthcoming visit of the XVIth Karmapa. Rinpoché’s approach was not one of “what funds do we have and what can we manage to do with those?” but one of outlining all the things we would need to buy, hire or do and costing it, generously, along with offerings, and then asking me,

“Now how are we going to raise this?”

Working in the administration at the time, I was well aware of our financial situation and possible incomes. The sum he mentioned seemed astronomical and I told him so. He just replied that all we needed to do was have faith and that it would come, through the power of pure intentions and our good karma. This was a position Rinpoché adopted throughout his years as hands-on leader of Samye Ling. He would aim high, trust in faith to magnetise necessary resources (human or material), be happy when it worked but also accept the karma of the situation when it did not work, knowing that, in the process of trying, we had done our best and accomplished some good karma anyway.

In particular, his approach to fund-raising was to trust in faith. He was not particularly at ease, in the subsequent era of Samyé Ling, when outside professional fund-raisers were hired and an internal fund-raising team formed, mainly during the development of the Holy Isle project. He was uncomfortable with the many mail-outs and so forth but, in another way, recognised that his preferred way (pure faith) only worked when he was at the very centre of the mandala, with his unique karma. Now he had withdrawn being abbot and was investing his main energies in other areas, different approaches would be needed to suit the new circumstances, the new team and the new abbot.

Rinpoché believed in the vacuum effect: that by creating a new project, resources would be drawn in and that these would not necessarily drain existing resources but would rather attract new ones. He sometimes compared this to the common household experience whereby if one totally clears a table-top, people will very soon put things on it. They cannot resist it. The table top remains empty only for a short period. In his own workspace—known officially as the Conference Centre and unofficially as the Cottage—he had had made the most extraordinary, massive round table, which broke down into many modular units. Many hours were spent organising, tidying up and then filling up those table tops. For him, it was a familiar and well-rehearsed example.

......continue to the next part of the story: the Samye Temple