Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Five: The Samye Temple

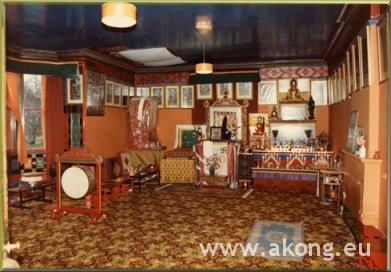

The Tibetan term for a temple, lha khang, means “a home for the sacred”. The temple is just that, being the main place for the various representations of the Three Jewels and Three Roots, as well, of course, for the activities of the sangha. Until the 1977 Karmapa visit, Rinpoché had “made do” with a heterogeneous setup: the temple or “shrine room” as it was known was the old gun-room of Johnstone House, a former hunting lodge.

The largest Buddha images came from donations and were of Burmese rather than Tibetan origin. The shrine room itself was relatively simple and became gradually decorated with a growing number of Tibetan thangka, as art-master Sherab Palden (often said in a single flow ... "Sherapalden") created them in his studio. There were only a couple of token texts, on the shrine. A few low seats in one corner sufficed for Akong Rinpoché, Sherapalden and Samten to perform the daily

prayers. This small room, probably less than 30 square metres, received many very eminent teachers for some twenty years. The growing numbers using it eventually extended out the door, down the corridor and into the main hallway, up the main staircase and even into the dining room, listening through a loudspeaker.

The largest Buddha images came from donations and were of Burmese rather than Tibetan origin. The shrine room itself was relatively simple and became gradually decorated with a growing number of Tibetan thangka, as art-master Sherab Palden (often said in a single flow ... "Sherapalden") created them in his studio. There were only a couple of token texts, on the shrine. A few low seats in one corner sufficed for Akong Rinpoché, Sherapalden and Samten to perform the daily

prayers. This small room, probably less than 30 square metres, received many very eminent teachers for some twenty years. The growing numbers using it eventually extended out the door, down the corridor and into the main hallway, up the main staircase and even into the dining room, listening through a loudspeaker.

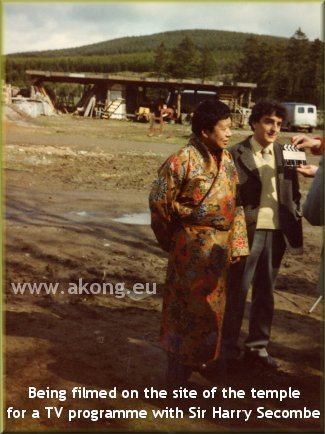

Akong Rinpoché was very wise to plan the Samye Temple when he did. The struggle for planning permission was a difficult one. The current regulation only allowed for building in a traditional Scottish style. Some councillors were horrified at the thought of an oriental temple, with pagoda roof, appearing in their Scottish countryside. It was only through the intervention of the local peer, Lord Tanlaw, that a breakthrough was made. Over the years, Lord Tanlaw has showed great kindness and been very helpful to both Akong Rinpoché and to Samye Ling. He became a friend of Akong Rinpoché. He pleaded with the council that it was only through the influx of people into Eskdalemuir, because of Samye Ling, that the local school and village shop had stayed open: in stark contrast to many other small Scottish valleys that were depopulating. His voice was heard and permission was given for the traditional temple, provided that it be hidden from the road by a large hill.

The site for a possible temple had been chosen during the Karmapa’s first visit—an area of forest on the northern side of Johnstone House. An unusual gift of fate had occurred concerning this. In 1973, Rinpoché had received the visit of a Sufi master who was travelling around Europe alerting people to a major cosmic change that would come with the passing of the comet

Kohoutek. Rinpoché had listened patiently to him and afterwards spoke from time to time of “the comic”, meaning the comet (Rinpoché never bothered to perfect his English and only sought to speak it well enough to be understood). When the comet did eventually pass, in January 1974, record violent winds swept across Ireland and Scotland and an exceptional mini-tornado downed a very precise line of trees in the woods next to what is now known as Fairy Hill. It then circumnambulated Samyé Ling, making the

old stone house shake violently, and took down scores of trees immediately to the north of Johnstone House, in what was a dense, mixed woodland at the time (and is now the site of Samye Project).

The site for a possible temple had been chosen during the Karmapa’s first visit—an area of forest on the northern side of Johnstone House. An unusual gift of fate had occurred concerning this. In 1973, Rinpoché had received the visit of a Sufi master who was travelling around Europe alerting people to a major cosmic change that would come with the passing of the comet

Kohoutek. Rinpoché had listened patiently to him and afterwards spoke from time to time of “the comic”, meaning the comet (Rinpoché never bothered to perfect his English and only sought to speak it well enough to be understood). When the comet did eventually pass, in January 1974, record violent winds swept across Ireland and Scotland and an exceptional mini-tornado downed a very precise line of trees in the woods next to what is now known as Fairy Hill. It then circumnambulated Samyé Ling, making the

old stone house shake violently, and took down scores of trees immediately to the north of Johnstone House, in what was a dense, mixed woodland at the time (and is now the site of Samye Project).

One large hardwood tree had a damaged major branch threatening Johnstone House itself. In the rain and the gale, Rinpoché insisted on going up the tree, with a chainsaw, in the light of the headlamps of the centre’s Land Rover manoeuvred into place by myself, and was giggling away without a care and with a sense of adventure, as some of the female members of the community were screaming and crying for him to come down, scared for his life. To make the scene even more dramatic, electric power lines had been brought down in that very clump of woods and they were still live and dancing in the wind, making sparks as they earthed from time to time. It was a truly apocalyptical scene. Rinpoché succeeded in cutting the branch and in getting back down safely. He had saved the roof from severe damage. Some two hundred trees had been blown down in less than one minute that evening. The revenue from their later sale enabled early work to be done on the Samye Temple site. It was truly impressive to see Rinpoché’s calm, courage and determination in a situation of urgency such as that.

Having obtained initial planning permission, the site for the four sides of the Samye Project needed to be marked out. To do this, Rinpoché chose the right day, from a Tibetan astrological calendar, and, not totally trusting the magnetic north of a compass, wanted to align the site exactly with the cardinal points of the compass by using the stars. Thus it was that on that starry night, he and the author took four fence-posts, some string and a hammer out onto the cleared forest

site. Under his direction I moved back and forth until I was, from his place of view, on the south-east corner of the Samye Project, standing under the Pole Star.

I duly knocked in a fencepost as a marker. Using simple geometry and string, the other posts were put in place. Rather cheekily, Rinpoché said that the size of the site permitted by the council was too small and that we should “massage” the measurement somewhat; which we did.

I duly knocked in a fencepost as a marker. Using simple geometry and string, the other posts were put in place. Rather cheekily, Rinpoché said that the size of the site permitted by the council was too small and that we should “massage” the measurement somewhat; which we did.

Long before the awakening to it of popular awareness, Akong Rinpoché was very concerned for the environment and in particular for the mineral resources under the ground and the animals and plants roaming on it. He was nearly always saddened by mining and saw it as something that would bring poverty and misfortune to the area or the country in which it was done. He believed in the benevolent or malefic power of “local spirits” and was happy for that notion to be understood either

as living beings or as natural energies—for him, the subjective interpretations that made people comfortable with the idea mattered less than the actual, tangible outcomes of damaging the earth. He did not like the coal mining in Scotland and later was appalled at the extensive gold and mineral mining in Tibet.

Once, when digging out some rock behind Johnstone House, I saw Akong Rinpoché, just arrived to inspect our work, take great pains to save and extract a daffodil bulb that was in the ground. Once he finally had it, intact, his face brightened and he grinned and said, “Make flower!” The loss of the scores of trees, due to the Kohoutek moment, had made the decision to totally clear the rest of the future Samye Project site easier

but Rinpoché nevertheless wanted to act in harmony with the land and the local spirits. There is a special ceremony for doing this, involving many prayers and offerings to those spirits before the first ritual breaking of the earth. He wanted this to be done by the yogi, Lama Gendun Rinpoché, and invited him to Samye Ling, to this end and also to teach, in 1979.

Once, when digging out some rock behind Johnstone House, I saw Akong Rinpoché, just arrived to inspect our work, take great pains to save and extract a daffodil bulb that was in the ground. Once he finally had it, intact, his face brightened and he grinned and said, “Make flower!” The loss of the scores of trees, due to the Kohoutek moment, had made the decision to totally clear the rest of the future Samye Project site easier

but Rinpoché nevertheless wanted to act in harmony with the land and the local spirits. There is a special ceremony for doing this, involving many prayers and offerings to those spirits before the first ritual breaking of the earth. He wanted this to be done by the yogi, Lama Gendun Rinpoché, and invited him to Samye Ling, to this end and also to teach, in 1979.

Akong Rinpoché also wanted, as is traditional in Tibet, to bury “treasure vases” at key location in the foundations of the temple. He requested relics for these from the Gyalwang Karmapa and his four “heart-sons” as well as from very senior figures in all the Tibetan traditions. The response was a kind donation of many rare relics from these great masters . These were placed in vases specially commissioned by him from Sonja Gerlings, the South African master-potter who had taken residence in Samye Ling. the relics were mixed with precious stones and rare substances. Each vase was buried with due ceremony at the various corners and power-spots of the temple and later covered by the concrete slab of the foundations.

Rinpoché hesitated about the foundations themselves for a long time. He had made provisional plans for it to house an underground shelter, in case of nuclear war. This disturbed the local council planners, who asked, “What does he know that we don’t yet?” In the end, Rinpoché did not feel it would be necessary and also realised how costly and time-consuming it would be to construct.

Rinpoché’s intense involvement in every aspect of the subsequent building of the temple, between 1979 and its opening in 1988, is being documented separately and will not be discussed in further detail here. The author had the pleasure of being Rinpoché’s personal assistant throughout this time and witnessed the patience, mindfulness, diligence and wisdom with which he dealt with architects, local council officials, his good personal friend and building advisor David Robison (whose contribution was invaluable), the totally-volunteer building team and everyone involved.

......continue to the next part of the story: Establishing High-Quality Dharma Artefacts